What are botnets?

The term “bot” refers to computer devices infected with malware under the control of a threat actor. When hundreds, thousands, or even millions of these infected devices are hijacked, they are referred to as a “botnet.” These botnets are used in many different ways: they can spam thousands of phishing emails at a time, spread malware to other computer devices to create new bots, manipulate online polls to go in a particular favor, and even deny services by flooding web servers until it cannot respond to legitimate requests.

How can a threat actor communicate with their botnet?

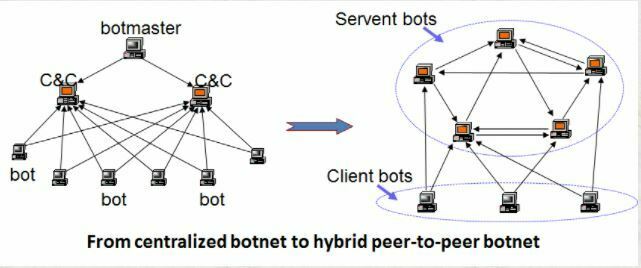

There are a couple of ways botnets can receive instructions from the threat actor controlling them. One way is through a command & control structure (C&C); this structure relies on commands given by the threat actor from a centralized location. These locations can vary: a website that the threat actor controls to relay instructions which bots interpret as commands, a third-party web page used to relay commands posted by the threat actor, and commands sent via blogs and social media posts. Threat actors can even use a Google Gmail account to create a draft containing the orders for the bots. Since the threat actor does not send the email, Google has no record of the commands.

Another way bots can communicate with each other is by using the peer-to-peer model. Threat actors are increasingly using this model because it has no centralized location for the commands, unlike the C&C structure. This model functions because each device works independently as a client and a server. The devices coordinate amongst each other to transmit and update information across the botnet. According to the FBI’s cyber division, every second 18 computers worldwide are part of botnet armies, which amounts to over 500 million compromised computers per year.

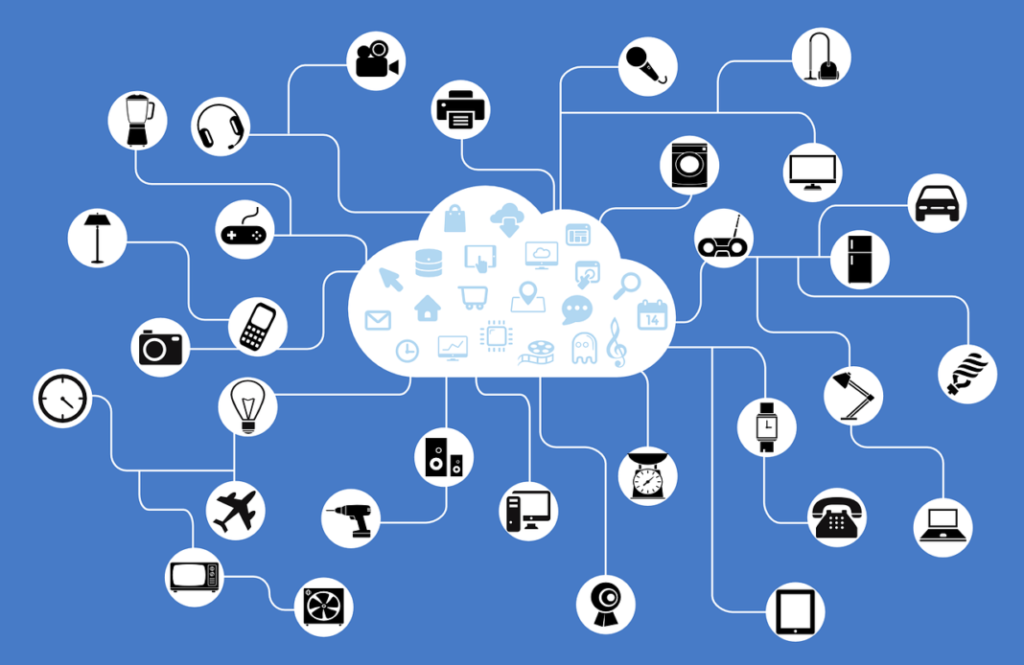

What types of devices are used for these coordinated attacks?

Botnets are only increasing in size as the amount of global IoT(Internet of Things) devices continues to grow in scale. IoT devices like connected cameras, refrigerators, and other smart appliances that communicate through the Internet, can fall victim to threat actors and become part of a botnet. IoT devices are now responsible for 32.72 percent of all infections observed in mobile and Wi-Fi networks – up from 16.17 percent in 2019. Although these devices are increasingly attacked and taken over by threat actors, the companies producing the machines are making little to no effort to secure them. These manufacturing companies have little incentive in securing their devices as it can slow down production. When they do try to harden their devices, it is usually through weak hard-coded passwords like “12345” and “Passw0rd”.

As a first step in securing IoT devices, the senate recently passed an act called the “IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act.” This act would require the federal procurement and use of IoT devices to conform to basic security requirements. In other words, the federal government would have a set standard for the IoT devices that they purchase for government use. These guidelines follow existing standards and best practices and would drive contractors to adopt these standards in the production of their IoT devices. This legislation can help shed some light on the vulnerabilities plaguing government IoT devices and consumer devices. I believe that this act can help pave the way for other laws concerning the lack of security in IoT devices.

Some infamous botnets:

One of the more famous botnets to date is the Mirai botnet. A group of college kids created this botnet to launch DDoS attacks against their university and, in a not-so-surprising twist, Minecraft servers. These college students designed a worm that infected routers and IoT devices. It was one of the first and largest botnets to implicate IoT devices on such a large scale. At its peak, the botnet had collected over 600,000 devices. They were able to do this because the infected devices used weak or no login credentials. As the botnet grew more prominent, the notoriety of their attacks got the attention of the authorities. To prevent this, the college students released the source code of the botnet in 2016 in the hopes it would distract the authorities with other Mirai botnet copies. Since the students released the source code, there have been many variants of the Mirai botnet, with the most widely known being Okiru, Satori, Akuma, Masuta, etc…

The Mirai botnet is just one of many types of botnets infecting devices. Although many botnets use their bots or “zombies” to send DDoS attacks, some threat actors steal information and send ransomware to the devices they corrupt for financial gain. An example of this is the Gameover Zeus botnet. This botnet was a banking Trojan that infected over a million devices. It stole banking information from the computers they infected while also offering other cybercrime groups access to the hosts so they could install their own malware. This botnet was also one of the first-ever to distribute a ransomware strain that encrypted files instead of just locking a user’s desktop. The FBI identified that the primary operator of this botnet was a Russian man named Evgeniy Mikhailovich Bogachev, which still has a $3 million reward by the FBI and has the biggest reward of any hacker.